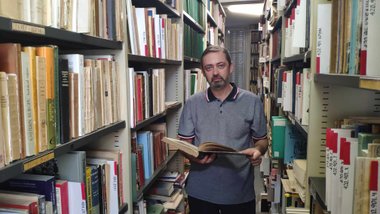

Expert: Russian World Doctrine Not About Christ, Principles of Orthodoxy, Salvation or Spiritual Growth, but Geopolitics

Contrary to some observers who I genuinely respect and whose thoughts I carefully listen to, I tend to treat the “Russian World” doctrine completely seriously. Without a doubt, it is not about Christ and not about the unscathed teachings of the Seven Universal Councils, not about salvation and not about spiritual growth, but about geopolitics. Indisputably, the details of this doctrine, which appear more and more clear, are capable of causing the turmoil of theologians and the indulgent smiles of experts in humanities and social sciences. The doctrine can be thoroughly criticized, and in the year since the last council, it has been done repeatedly.

Contrary to some observers who I genuinely respect and whose thoughts I carefully listen to, I tend to treat the “Russian World” doctrine completely seriously. Without a doubt, it is not about Christ and not about the unscathed teachings of the Seven Universal Councils, not about salvation and not about spiritual growth, but about geopolitics. Indisputably, the details of this doctrine, which appear more and more clear, are capable of causing the turmoil of theologians and the indulgent smiles of experts in humanities and social sciences. The doctrine can be thoroughly criticized, and in the year since the last council, it has been done repeatedly.

But the doctrine has a real sting. Its reality is not at all in the firmness of arguments and iron logic. And, if to talk about Ukraine, Ukrainians are dissatisfied in how their historic choice is unfolding. They became Ukrainians because they wanted to become sovereign subjects of history and not raw material for what Patriarch Krilll calls the “Russian World.” They decided that they have enough strength and talent to stop being “the periphery of the periphery” and take an independent part in world affairs. In short, they decided to build something more effective, human, and suitable for life than that creation which more often gave the world an example of how things should not be than a model of perfection.

However, the patriarch, since his visit to Ukraine in the summer of 2009, calls Ukrainians to reexamine this choice. He is holding for them an honorary place in the social sphere, promises to take into consideration their individuality and give them the right to talk with others “on behalf of a powerful civilization.” And places before Ukrainians already rather concrete tasks: “to build a civilized consciousness,” strengthen their shared history, begin the process of integration, transform Kyiv into “one of the most important political and social centers of the ‘Russian World.’” The patriarch honestly says that it is promoted by “historical conditions.” Under such favorable conditions one must understand the change in the political situation and the disillusionment of a large part of Ukrainians in the results of the first twenty years of independence. In a different case, the patriarch’s doctrine would not have even remained as a subject only for academic discussion, but, more likely, would have received a lashing from the press. But, nonetheless, it is unclear why Ukrainians should refuse from the historical subjectivity? For the sake of the usual eschatological project? They still haven’t come to their senses from participation in previous ones. Why in the global discussion of cultures and spiritual traditions should they not speak on behalf of themselves? To decide where and how fast to integrate? Why does participation in this project join them with the “highest, all-human level of social life, which is possible in the sinful world?”

The doctrine, however, which is more similar to the teachings on civilizational determinism than to the theological conception, nevertheless remains a challenge for Ukrainians because it comes from their inability to develop independently and reach “prosperity and assurance in the future” outside of the community where they could not reach this “prosperity.”