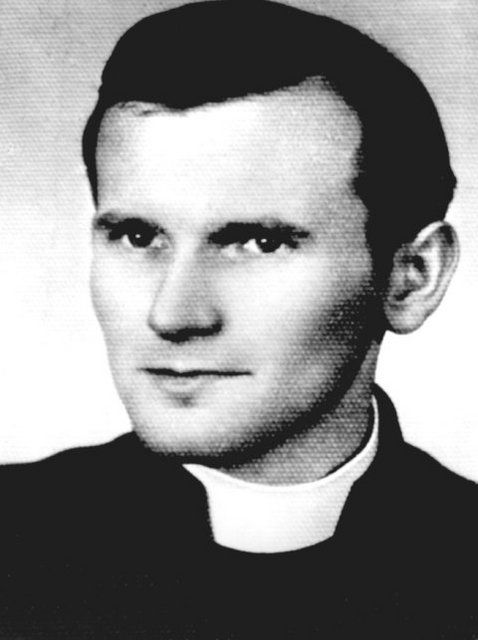

Karol Wojtyła appears in Vatican Archives

Karol Wojytła (1920–2005) is arguably the most famous Pole in history but he also made a major impact on Ukrainian history, especially on the fate of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. Even before his election to the papacy as John Paul II in October 1978, Wojytła had become a pivotal pubic figure in his homeland where, as Archbishop of Kraków, he held the highest offices in the Church, second only to that of Polish Primate. A few days ago, I discovered a letter written in September 1946, which might represent the first time he was brought to the attention of the Vatican.

Wojtyła’s path to leadership was anything but standard, and is perhaps better described by the old Christian proverb “The ways of Providence are infinite.” To be sure, his call to priestly service happened in a period of wartime terror, where millions were slated for destruction by racial hatred and totalitarian dictatorships.

The Nazis not only sought to destroy the body, they also sought to destroy the soul. While the Jewish people were their particular focus, they also targeted others for destruction, and among the first victims of Hitler’s racist plan was Poland. Hypothetically, it would be interesting to observe the reaction of a Holocaust denier faced with the mountain of testimonies in Vatican archives. Combing through the Foreign Affairs section of the Archive of the Secretariat of State, a researcher is overwhelmed by reports from diplomats, military chaplains, church and civic leaders, many of which were eyewitnesses to the genocides and ethnic cleansings being perpetuated in the name of the Third Reich.

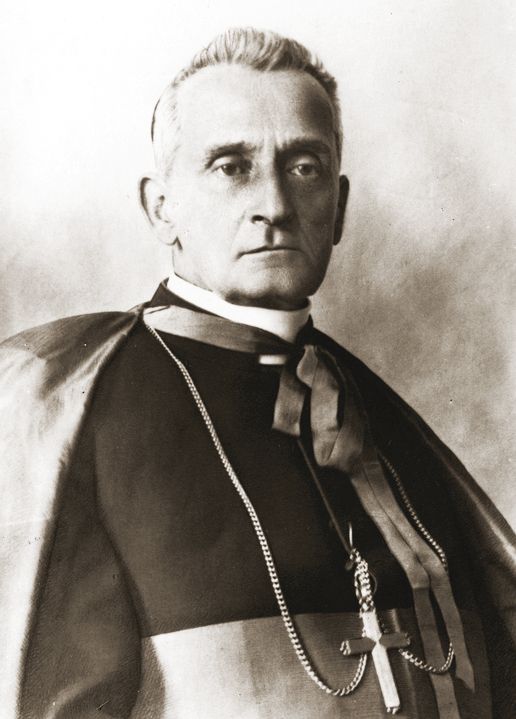

From 1942, reports began to observe that German atrocities against the Jews pointed towards an intention to bring about their complete annihilation. But Hitler’s eventual plans for the Slavic peoples were not entirely dissimilar. While the Catholic Church was barely tolerated in western Europe, in the east it was being destroyed. Polish bishops, clergy, and religious were imprisoned and killed, seminaries and universities were shut. Church leaders had to find creative ways to provide ministry to their suffering flocks. The Archbishop of Kraków, Adam Sapieha, demonstrated fearless strength in dealing with the occupiers, who were perhaps a little in awe of a man who held the rank of prince of the Holy Roman Empire.

Unlike like his protégé Wojtyła, who was of humble origins, Sapieha came from an ancient noble line and was groomed for the highest offices in the Church from an early age. He studied in Vienna, Kraków, Lwów (Lviv), Innsbruck, and Rome. From 1905 to 1911, he worked in the Roman Curia as consultant on Polish matters. In November 1911, he replaced Cardinal Jan Puzyna, as Prince-Bishop of Kraków. In the normal course of things, the Austrian Emperor would have asked the pope to name Sapieha a cardinal (as per the imperial prerogative). Then came the First World War, the fall of Austria-Hungary and Polish Independence. Together with his friend Archbishop Teodorowicz, Sapieha went against Vatican’s plans for the Polish Church and opposed the papal nuncio, Achille Ratti. After Ratti was elected Pope Pius XI, in February 1922, Teodorowicz and Sapieha were forced to resign their seats as senators, and remained under a partial cloud, as far as Rome was concerned, until the end of the pontificate. The two prelates were also in opposition to the Piłsudski dictatorship and Sapieha had his windows broken by devotes of the late dictator, when he moved the latter’s tomb to a less prominent part of the Wawel cathedral crypt. In 1939, Pius XI and his successor Pius XII refused Sapieha’s resignation. Then, the outbreak of the Second World War changed everything.

The Archbishop of Warsaw had died in 1938 and the Primate, Cardinal Hlond, was prevented from returning from abroad. Sapieha remained the senior churchmen with the burden of acting as the leader of the bishops within the country. This brought him up against German authorities, who had slated his church and his people for destruction. His reputation quickly changed from unpopular or unpatriotic to being considered a national hero.

On 2 November 1942, Sapieha appealed directly to the governor of German-occupied Poland, Doctor Franck and, the following year, convinced the bishops still at liberty to join him in a second appeal. In the name of humanity, the episcopate decried the killings, arrests, and restrictions on church ministry. They asked for Roman Catholic seminaries to be allowed to reopen, but a response from Berlin was not forthcoming. Their pleas were heard by Pius XII, who first instructed his nuncio in Berlin to submit a diplomatic protest to the German Government but the note was sent back. Further messages elicited a dismissive reply from Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German Foreign Minister.

Having failed to influence the German government directly, Pius XII protested on behalf of the Church in Poland in an allocution to the College of Cardinals in June 1943. Translated into Polish, it was read from the pulpit in Warsaw Cathedral. His messages received effusive thanks from the episcopate, from Prime Minister Sikorski, and President Raczkiewicz, who declared himself “profoundly moved by Your Holiness’s words.”

In the meantime, imprisoned and murdered priests had to be replaced, Sapieha opened an clandestine seminary and informed Rome of the situation. When Pius XII learned of the seminary, he instructed the Secretariat of State to send the following message to the Archbishop: “The August Pontiff, with good wishes and fervent prayer, supports this initiative, which is so important for the future of the Church in those regions.” Little did the pontiff know how important the underground seminary would become for the entire world it was already preparing his successor in the Chair of Peter.

No sooner had the Nazis been defeated when Poland, abandoned by the European Allies, was forced by the victorious Soviets to accept another totalitarian regime. Adam Sapieha was finally created cardinal in February 1946 and, undeterred, remained at his post until his death, in 1951. In the meantime, he began to prepare the Polish Church to bring forth new laborers for the spiritual harvest.

On 22 September 1946, Sapieha sent the following letter to Monsignor Domenico Tardini, head of the Secretariat of State’s section for Extraordinary (Diplomatic) Affairs:

Most Illustrious Monsignor,

You will easily understand that we very much want to send our seminarians to Roman universities in order to give them the possibility to perfect their studies and to live, for a time, in the capital of the Church. However, in order to enter Italy, it is necessary to have permission from the Italian Government and to be provided for financially. Wherefore, I am asking if, in some way, You could obtain this permission for us. As to being provided for, they would stay at a College that would provide this assurance.

For the moment, we hope to be able to obtain passport for two students, that is, Karol Wojtyła and Stanisław Starowiejski, students of Kraków Diocesan Seminary. I apologize, Monsignor, for disturbing You, but it was necessary to take advantage of the occasion.

With the two seminarians' curricula vitae enclosed, Cardinal Sapieha’s letter arrived at the Vatican on 1 October 1946, although Monsignor Samoré was at a loss to explain how it had been delivered. On 4 October, Tardini presented a nota verbale to the Italian Ambassador to the Holy See, asking for his assistance and mentioning the names of the two students.

For a seminarian to be ‘mentioned in dispatches’ by name is a rare thing. And this letter might well represent the first mention of Wojtyła in correspondence with the Apostolic See, contained in Vatican archival collections. Sapieha had not specified but, in fact, neither seminarian had yet been ordained. Wojtyła was to receive minor orders and subdiaconate on 13 October, diaconate on 20th, and priestly orders on 1 November. He was already in Rome on 15 November and registered at the Pontifical Athenaeum (later University) of Saint Thomas Aquinas (known as the Angelicum) on 26 November. This author, who studied Philosophy and Theology at the same university, was privileged to have been present in 1994, when John Paul II came to the Angelicum’s aula magna, which had been renamed in his honor.