The east is the east and the west is the west. They both meet in Lviv.

77% of Ukrainians have never been outside of Ukraine and every third inhabitant of our country has never left his/her home region. The students of Lviv (in particular those of the Ukrainian Catholic University), took the initiative to overcome the animosity and ignorance between inhabitants of the east and west of the country by inviting their fellow colleagues from various cities in eastern Ukraine to Lviv. The first group of students arrived from Donetsk. Some 1,200 kilometres separate Donetsk from Lviv and because train travel in Ukraine can be very long, the trip lasted approximately 20 hours. The two cities are often polarized by politicians. Donetsk is depicted as a Russian-speaking industrial powerhouse while Lviv tends to be seen as a Ukrainian-speaking tourist destination. Two distinct mentalities, histories, and national identities are at play. Can a weekend spent in Lviv transform the way of thinking of Donetsk residents?

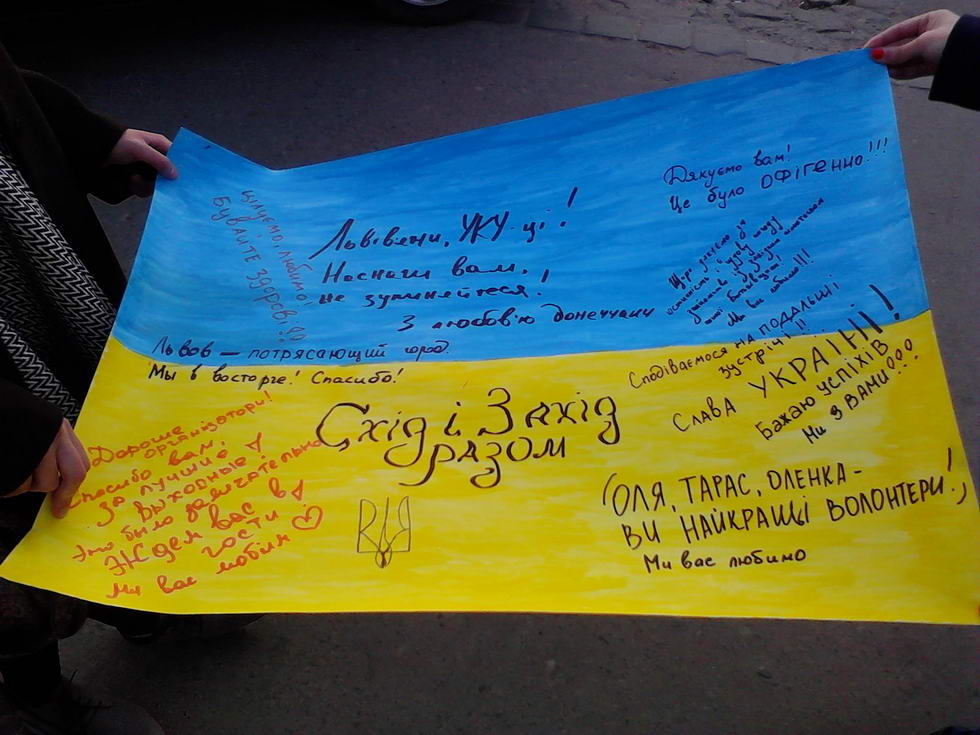

Although more profound transformations take longer to manifest themselves, organizers noticed that a certain kind of resentment was conquered. They feared that by initiating the campaign entitled “From east to west,” few would be willing to come to Lviv due to the existing stereotypes and complicated political situation in the country taking into account that Ukraine is practically on the verge of an undeclared war with Russia during the course of which Crimea has already been lost, the east and south of the country are under a constant threat of separation and society as a whole is still in a state of post-traumatic shock following the bloody events on the Maidan which claimed the lives of nearly one hundred people. Nonetheless, the young people of eastern Ukraine turned out to be much more open than the older generation. During the first week since the campaign was announced in social networks (this was in mid-March), some 800 people registered to participate. At this point in time, the number of people willing to participate has reached 2000, forcing organizers to establish a quota. As of now, only current students who have not yet visited Lviv can participate.

Many students have had to overcome inner stereotypes and the discouraging opinions of those in their immediate surroundings, most notably their parents. Valeria Svischuk, a fourth year student in journalism from the Donetsk National University, claimed that she practically “ran away from home to come to Lviv since her parents would not let her go, claiming that Lviv was a scary place to visit.” In this regard, it must be said that some parents prohibited their children from making the trip. Overall, during the first weekend of a campaign that will last all spring, 80 students visited Lviv. More than one thousand students from eastern Ukraine are expected to visit Lviv during the course of the campaign.

According to Julia Hnativ, the campaign coordinator, “everyone who comes here is an achievement in and of itself. In coming, a person overcomes his or her own fear and does something new which will he or she will later take back home with them. Both eastern and western Ukraine need this in order to better understand one another.”

During their stay in Lviv, visitors had an opportunity to better acquaint themselves with a number of the city’s different traditions which happens to be among the top ten places to visit in Europe in 2014 according to the British guidebook Rough guides. They were also able to indulge in its culinary particularities, meet local students as well as the mayor – Mr. AndriySadovyi. It is worth noting that the city of Lviv, whose motto is “open to the world,” enthusiastically supported the students’ initiative. The city’s business community was also very helpful – hostels, restaurants and cafes all pitched in while guides offered excursions free of charge.

During their stay in Lviv, visitors had an opportunity to better acquaint themselves with a number of the city’s different traditions which happens to be among the top ten places to visit in Europe in 2014 according to the British guidebook Rough guides. They were also able to indulge in its culinary particularities, meet local students as well as the mayor – Mr. AndriySadovyi. It is worth noting that the city of Lviv, whose motto is “open to the world,” enthusiastically supported the students’ initiative. The city’s business community was also very helpful – hostels, restaurants and cafes all pitched in while guides offered excursions free of charge.

Visitors were impressed by Lviv, its tourist attractions and people who were by no means hostile but on the contrary, open and willing to show them their city.

Dasha, a student from Donetsk states: “the situation in Donetsk is more tense than in Lviv. Suspicious and aggressive individuals prowl the streets. Many locals are simply too scared to leave their homes. Upon on our return to Donetsk, we will use the mass media to talk about Lviv and how the Russian mass media paints a false image of the city.” The Russian mass media often talks about how the city’s residents are unfriendly to Russian-speaking people. Nevertheless, students discovered first hand that this is simply not the case. Although Lviv is a Ukrainian-speaking city, its residents are accepting of Russian-speaking visitors (it is worth noting that nearly 20% of the city’s population are ethnic Russians). In the words of BohdanKarasyov, “no one even made a fuss about me speaking Russian all the time although I can also speak Ukrainian. I never felt albeit the slightest hint of animosity or aggression.”

It must be said though that visitors enjoyed switching to Ukrainianand learning about the culture of the city which, as it turns out, unites and not divides different parts of Ukraine.

The campaign’s organizers also learned quite a bit from their guests from Donetsk.

“We met young and innovative people who are by no means indifferent to what is happening in Ukraine. They want things to change for the better. They understand that for them, much is still at stake and they are ready for new encounters and dialogues” says Natalia Klymovska, head of the department of development at the Ukrainian Catholic University.

It is important that these young people from Donetsk were able to meet their counterparts and adherents from their own city and communicate as well as discuss their plans for the future in order to organize similar campaigns and projects in the years to come.

As Natalia Klymovska pointed out, “they come from different universities all around Donetsk and got to know one another in Lviv. They say saw and experienced something together. They are now ready to work in Donetsk in order to create a civil society there. This simply underscores the fact that the east needs to be in contact with the west and vice versa.”

Over the next few months (March, April, and May), students from Lviv will be hosting guests from Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, Luhansk, Dnipropetrovsk, Kharkiv, Mariupol, KryvyiRih and Crimea. Although organizers understand that 1000 guests from eastern Ukraine will not be able to cardinally change the situation, they hope that they will become catalysts of change that will gradually bring down stereotypes and hostilities that persist among Ukrainians. The idea that students from Lviv should also travel to eastern Ukraine and the cities of Donetsk and Luhansk in order to better familiarize themselves with this part of the country was raised during the first weekend of the campaign. This is but a small step to better understanding one another. With this campaign, new friendships have already been made between Lviv and Donetsk notwithstanding the 1,200 kilometres that separate the two cities, the 20 hours of travel and the different political problems and divergences between eastern and western Ukraine.