The four seasons at the monastery of Chevetogne

The Monastery of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross in Chevetogne, Belgium, was founded in 1925. This Catholic monastic community lives according to two rites — Latin and Byzantine. The monastery sees its vocation in promoting the unity of Christians — Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants. Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky played a particular role in its foundation.

Autumn

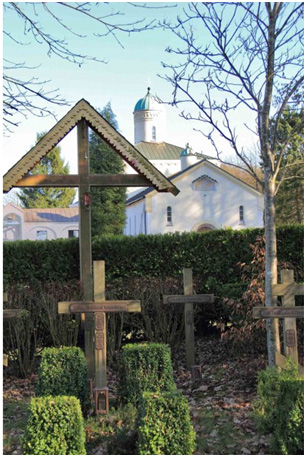

The main road to the Chevetogne monastery runs past the monastic cemetery. The traveller, upon arriving at the monastery, first encounters the dead. But death does not reign here. Trees and bushes rustle, the earth is covered by fallen leaves, the lamps modestly shine. There are no monuments or magnificent tombstones — only simple crosses with men’s names on metal plaques. There are almost four dozen of them — Belgian, French, Dutch, German, Ukrainian, Russian, English…

The delicate, unostentatious beauty of this cemetery, its modest and carefully woven aesthetics is an attempt to oppose death through order, harmony, and grace. Instead of chaos and disintegration, calm, systematic work, measured rhythm, and daily discipline. Instead of fear of death, there is a quiet conviction that life does not end. Instead of panicked flight — an eternal serenity under the rustle of leaves, a leisurely year-round cycle of nature…

The Chevetogne monastery is of the Benedictine tradition and lives according to the motto ora et labora (“pray and work”). They approach work here as they approach prayer: one must be concentrated, without haste and greed The founder of the tradition, Saint Benedict of Nursia, taught that monastic artisans should work not for selfish enrichment, but “to glorify God in all things” (ut in omnibus glorificetur Deus). Therefore, tending to the cemetery, courtyards, orchards, or gardens, cooking, icon painting, attending to the monastery shop, library or website, as well as intellectual research or teaching — all these activities can be a means of salvation. They structure time and space, organize thoughts and actions.

Belgian November is synonymous with humidity, cold, and the dense darkness of the evenings. Cold and lack of sun affect the human psyche as inhibitors: they slow down and hamper thinking, they can be oppressive and cause depression. That is why the hyperborean peoples paint their houses in bright tones and make necklaces from colourful beads. The white and brick-red walls of the monastery’s churches and cells are like a man-made fortress, besieged by glacial, dark elements in the autumn nights.

In Chevetogne, the first cure for the soul and mind is prayer: no matter what season, at 6 o'clock every morning begins with Matins. Dawn is still ways away, but the first candles are already lit, the first quiet singing is heard. Combatting depression is the daily quiet joy of meeting the living God. Against the cold — warm red and gold tones in the interiors of the churches, the cosy light of the oil lamps. Against the monotony and the greyness — the high poetry of the psalms and a variety of Byzantine stichera and heirmoi daily. Prayer sanctifies weekdays, taking them out of the ordinary.

Winter

There are two churches at the Chevetogne monastery: Latin and Byzantine. Of the twenty-seven monks, about half belong to the Western rite and the rest to the Eastern rite. On Sundays and some holidays, the entire monastic community participates together in the Byzantine worship services. This is how this monastery was conceived by its founder, the Belgian priest Lambert Beauduin: as a school where Roman Catholics could study the spirituality of the Christian East and find ways of reconciliation and unity between the Churches.

One of the winter holidays — Hypapante, Sretenie, the Encounter — has been celebrated in the monastery together with the Paris Eparchy of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church for the last five years. Since 2015, the Eparchy has been holding clergy and laity sobors (councils) here, which always occur in late January – early February. The veterans of these sobors are well familiar with the look of the monastery in immaculate white snowdrifts. The first to get up in the morning for the divine service traces the first beads of a prayer rope with their footprints in the snowy lane leading to the temple. Bishops, priests, monks, laypeople — no one will resist the temptation to build a snowman or throw a snowball at their neighbour!

On the eve of the Encounter (the eve of February 2, according to the “new,” Gregorian calendar), a Ukrainian bishop usually presides at the evening service. The solemn and tranquil Vigil lasts more than three hours, combining Vespers and Matins, helping the members of the Church to mindfully enter into the Feast of the Encounter — with God and one another. In the Orthodox tradition, it is not possible to imagine a great feast without a vigil, and many pilgrims will come to Chevetogne to take part in this splendid service.

Already at six o'clock in the evening the monastery is buzzing with quiet but focused preparation. A quick dinner, a silent rehearsal of singing, a rustling of cassocks, and hurried strides of feet over the granite tiles... Church Slavonic, French, Dutch, Ukrainian and other languages will be heard at the vigil. Everything should be ready in advance — texts and notes, the mandyas, the crosier and rhipidia, candles and incense of the monks’ handiwork.

There are dozens of varieties of incense — sandalwood, musk, coniferous, citrus and floral; from the classic Damask Rose to the unexpected Chinese Osmanthus with a hint of apricot. Just as the icon teaches us to contemplate correctly and the liturgical music to listen properly, so does the good incense foster our sense of smell, says the local “perfumer,” Father Cyril.

At half past seven, the first exclamation:

– Arise!

And we forget about the clock, the fatigue, the snow-covered darkness behind the walls. All that remains is singing — at once gentle and penetrating, powerful and incorporeal; white smoke of the incense, shimmering faces on the icons. And a yearning desire to be with Him.

“Come, let us worship and fall down before Him…“

Spring

Spring is announced by the beginning of Lent at Chevetogne monastery. The black trees and roads contrast starkly in the midst of the wet snow — and the Byzantine church is already dressed in the dark veils, the melodies are becoming more sombre, and at the entrance to the temple the monks and pilgrims begin to make three great prostrations to the ground.

Father Maxim of Chevetogne says that Lent is an opportunity for us to learn to live “vertically” in the pursuit of heaven; to practice the habit of getting up every time we fall. Kneeling with the deepest bow, we are conscious of our sins, we repent and ask forgiveness for them. But after every fall we get back on our feet — again and again, many times a day. This “physical training” of fasting affects our body, and especially our spiritual life.

How paradoxical: as nature recovers its power and beauty after a long winter, Eastern Christians do the opposite, they “turn down the volume” and “slow down” in their lives. We give up food, entertainment, and pleasure; we silence the sounds that surround us all year long to try to hear the voice of God in silence. The days get longer and warmer, the sun rises — yet we stubbornly choose dark colours, our liturgical singing becomes minor, ascetic. Together with Christ, who heads to His Passion in Holy Week, we reach the lowest levels of being, freeing ourselves from everything minor to focus on the one thing needful…

Great Lent is our voluntary diminution, subduing, self-restraint, so that after seven weeks, Paschal joy will burst out — like an apple tree, suddenly effervescent with white blossoms after the coming of warm days.

Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh called Lent the “spring of your soul.”

Pascha is the eternal spring of humanity.

Summer

The forty days between Easter and Ascension are a period “between earth and heaven.” This is the name of the disc of chants from Pascha and Ascension, which was recorded by the choir of the monks of Chevetogne. The disc’s liner notes tell us about this period: “[It] is like a single great feast day where Christ, Son of Man and Son of God, appears and is present among his followers, the sons of men, in order to prepare them to become completely Sons of God. The singing that characterises this period recalls feelings of joy, of reassurance, of triumph and of loving-kindness.”

Summer at Chevetogne is light-hearted, soft, emerald green. Worship services pass under the chirping of birds. In the middle of the day one hears the brouhaha of children from the outdoor pool a kilometre from here. Many monks and guests work in the garden and orchard. Alongside the Western Benedictine tunic and the Eastern podriassnik can be seen T-shirts, jerseys, and jeans.

As Compline ends on a summer evening, the “tranquil light” setting in the west still fills the church through its doors and arched windows. In the Byzantine church, Pod Tvoyu Milost (“Beneath Your Mercy”) is sung before bed, and in Latin — Salve Regina (“Hail Holy Queen”).

In July, the monastery celebrates Benedict of Nursia. Around this holiday, its oblates — laypeople and clergy, women and men of all ages and status — come to the monastery for an annual one-week meeting. They are not members of the monastic community, but they have a special connection with Chevetogne and try to be good Christians in their lives — in their family, at work, in public affairs, etc. In various ways, the oblates support the monastery and experience certain elements of monastic spirituality.

In the summer of 2016, the French TV channel KTOTV filmed the movie “May They All Be One” (with English subtitles) about the Chevetogne monastery as one of the centres of the ecumenical movement. In this movie, ninety-three-year-old Father Nicholas joyfully sings “Christ is risen” in Greek, walking into the monastery cemetery overgrown with lush greenery. Father Philip, the abbot here for eighteen years, feeds grain to the poultry and gleefully states, “I cannot imagine the Kingdom of God without ducks and bees!”

Father Thaddeus reflects on ecumenical relations: “No matter how hard we try, my or your narrative will never be adequate to exhaust the reality of the gift God gives us in the celebration of the Mystical Supper or the Eucharist. But is it really that important? Yes, it's important to think about and discuss these issues, but it's not the end of the world if our conclusions are not identical.”

Through prayer, hospitality, intellectual and physical work, fostering authenticity, beauty, and a culture of dialogue, the Chevetogne monastery continues its quiet struggle — to bring the unity of the Church of Christ closer. The fruits of this ministry ripen slowly. But members of the monastic community do not expect quick sensational results.

They remember the words of their founder, Lambert Beauduin, written almost ninety years ago: “Our generation, and, alas, probably, many of the following generations, will not know the desired unity; we must resign ourselves to this great ordeal and acknowledge ourselves unworthy of the grace of reconciliation.”

“When the Church of Christ receives the great beneficence of reconciliation, then we will belong to it more intimately and still more fully in glory: this suffices for us and fulfils us.”

All photos are from the website of the monastery.

By Olga Vokh

Translated from Ukrainian by Deacon Daniel Galadza