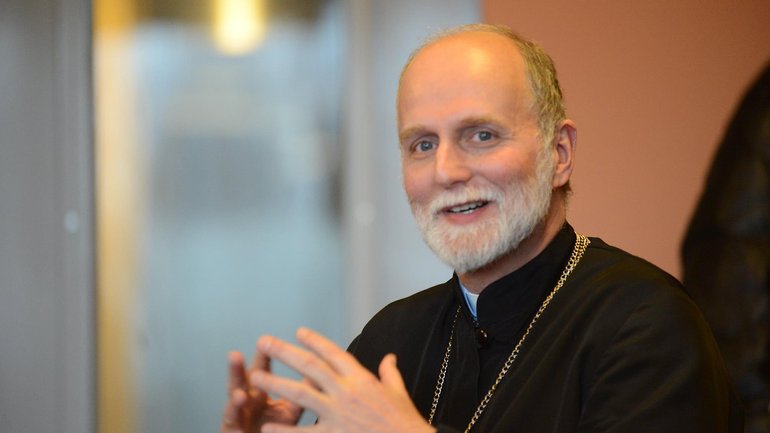

The one who invites to discover the depths: Borys Gudziak turns 60!

It seems that only recently we were congratulating the hierarch on his 50th birthday, remembering how we met him. Since then, much has changed in his life, the life of the UCU, UGCC and entire Ukraine. What remains unchanged is the optimistic and creative mindset, sincerity and openness, strategic vision and prayerfulness, the ability to listen and empathize.

On the eve of the anniversary, RISU asked various people who know Metropolitan Borys in different roles (such as scientists, former students, priests, staff, public figures, etc.) to share their impressions of him.

On our part, we sincerely wish you, dear Bishop, to remain such an energetic and young spirit, healthy and joyful for many more good years!

The sacrifice of a scientist

Igor Isichenko, Archbishop Emeritus

The greater our talent is, the greater the sacrifice God expects of us. Multiple and varied talents of Bishop Borys Gudziak also determined the dimension of his sacrificial gift to the Church. The talent of a scientist became such a gift.

We met at the Shevchenko Institute of Literature over thirty years ago. I had previously defended my dissertation and was preparing a monograph for publication. A young doctoral student from the United States came to Kyiv to collect material for his work on the history of the Brest Union. The Department of Ancient Literature, headed by Oleksa Myshanych, was perhaps the most open in the network of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR for contacts with diaspora science. Hardly any humanities scholars from the West who were still rare could ignore a hospitable room at 4 Kirova Street (now Hrushevskoho Street). Borys Gudziak was probably the youngest of them. Already in a short conversation, he gave the impression of an intense, self-motivated personality who knows how to listen, observe, and accurately formulate thoughts.

In the 1990s, we started seeing each other regularly in Lviv. I had the honor to attend the inauguration of the Institute of Church History and to join the large-scale project of the Brest Readings, with which the newly established institute commemorated the 400th anniversary of the Brest Union. The creative atmosphere of academic dialogue, friendly and extremely polite, calm discussion of controversial issues of the past contrasted with the already familiar to me at the time the intransigence of religious discussions in post-Soviet Halychyna. Strategic foresight of the institute director, Borys Gudziak, was evident in everything. He created a new culture of not only scientific but also social dialogue. Unfortunately, this culture is still not very widespread in Ukraine.

Soon a fundamental work was published, summarizing Gudziak's research studies: "Crisis and Reform: Kyiv Metropolia, Constantinople Patriarchate and the Genesis of the Brest Union" (English 1998; Ukrainian 2000). It defined the criteria that the national historians of the Church had to follow, without hiding behind their confessional affiliation and provincial upbringing. The author gave an example of a calm, impartial, and highly consistent search for the truth based on reliable historical sources without pathetic ideologues and subjective assessments of individuals. A mature, talented scientist entered the academic world of Ukraine, from whom more and more new publications were to be expected.

Already in 1995, Borys Gudziak shared his hesitations with me. The necessity to take the gown was looming, which was a logical step for the organizer of the Ukrainian Theological Academy. It also entailed significant adjustments in life rather than adjustments to some daily routine - Borys was a real ascetic in his secular status. He would have less time for scientific research.

The choice was made. Borys became a priest, then a bishop. He revived the LTA together with like-minded people and transformed it into the prestigious UCU, headed and virtually reconstructed the Western European Eparchy of the UGCC, and then returned to the United States as the head of the UGCC in that country. He could only dream of the library work and the comfortable office. Scientific talent became a sacrifice made voluntarily and consciously for the Church.

I feel pity for that. I feel sorry for the unwritten books and unrealized personal researcher dreams of Metropolitan Borys Gudziak. But I understand all the incommensurability of academic studies and powerful creative archpastoral ministry, which shapes the future of the Kyiv Church and all our people. I just want the Church and the people to appreciate this sacrifice at its real value.

* * *

The rector who infects with the virus of faith

Vira Biy,

Senior Business Development Manager, N-iX company

My classmates and I were lucky to know Bishop Borys from the first years of the LBA-UCU restoration. Back in 1996, then still very young, but already a well-known scientist from the United States, who became vice-rector of the LBA, simply broke all possible patterns of our youth ideas about what should the second person after the rector at the university be like. This energetic young man, who was very nice to us, young students, brought with him a special virus into the university - a multifaceted and compelling one. However, it was clear to us as the students (and the Bishop constantly reminded us of this!) that this university is a grand experiment, being held in rather challenging conditions. And we, perhaps being its the main participants, had no choice but to believe and show resilience, stubbornness and the same experimental nature in our completely non-trivial studies.

For as long as I can remember the Bishop in LBA, he always radiated a special faith, as if he foretold a good future. It was somehow magically coming true - we were never bored with him, and we were never afraid that suddenly everything would stop or fail. However, somewhere it was intuitively clear that behind these successful accomplishments was a great deal of work, the unceasing vigilance of both the Bishop and the whole small team around. This power of faith and the desire to participate in this great construction of a "new, different" university was a highly contagious virus.

And something exciting was being built, something truly unusual, new, which stubbornly resisted and went against the mainstream of the old Soviet educational system, and many in this system, who have not yet lost critical thinking, also "infected" with this virus of belief in the possibility of building new adequate learning paradigm. We, the students, felt all this "tension" with the system, which very often resembled of the battle of David and Goliath. And even directly participated in some such "battles", as, for example, a very active performance of our students in the actions "Ukraine against Kuchma": the then Father Borys actively supported us and personally went out to the students, in a joint short prayer blessed all who then went line up for a student protest.

Thus, his rector tenure was non-standard there and went beyond the established vision in our post-Soviet space of who the rector is, what his public profile should be like. In particular, the Bishop has always been naturally close to students. He often approached students simply to greet and ask about everyone's life, about any challenges, needs or interesting things that happened in Lviv or Ukraine. He could ask for help, give advice, joke, could quarrel or scold, but did it out of love. The Bishop came to our summer schools to stay with us longer, get to know each other better and, if possible, play basketball together. His contact with students never took place for a show or self-promotion - his sincere desire for closer communication with no decorations with us showed how deeply the Bishop lived the idea of the university and cared about the lives of students. Later, as the university grew, the Bishop repeatedly regretted that he simply did not have the time to embrace all the students for a more personal conversation physically. Sometimes it revealed itself in unexpected ways of socialization, such as to suddenly play snowballs with the whole university at the Bishop's initiative.

A very interesting student experience was the course of Bishop Borys "Christian Spirituality in Postmodernism." At the time, for us, 'green' students who recently graduated from ordinary soviet schools, it was not only a very unusual format, as the curriculum included, for example, a lecture on rock music and various informal communities, but also the fact that someone wanted to speak with us about fundamental things on equal terms, have a discussion and share their experiences. The bishop strongly encouraged students to think critically, to have the courage to have their own opinion and make mistakes, and to take responsibility for their arguments and open discussion. This obviously became an integral part of the greater paradigm of honesty and transparency in education from the beginning, and a sort of business card of the university, it was a challenge for all of us, in particular, for me at some point. In the end, this made UCU a "pain in the eye" and a kind of beacon for many other universities.

After all, the Father was a good pastor of this then still small university community: with him, we learned to seek the truth, to pray, to be open, to think critically, sometimes to make mistakes but to try, forgive, and lend a hand to those who stumbled but stubbornly moved on, following his "Strive for the great"...

And you? Have you ever thrown snowballs at your rector?

* * *

Roman Zilinko,

art critic, head of the department of Andrey Sheptytsky National Museum in Lviv

My classmates and I were part of the third enrollment at the Lviv Theological Academy. It was 1996, just five years after the collapse of the Union. So we get to this new institution, and we still do not understand anything, we do not know what everything will look like, prospects are illusory, in the end, like everything happening around. The academy at that time was still in the premises of the former kindergarten on Kleparivska street, and the new premises at Sventsitskoho Street, where they were to move soon, was not in a state where it was possible to study comfortably. There were many such unknown, undiscovered, and uncertain things. But there were people, even People! The belief that everything would be fine in this environment, which was formed around the Academy, tremendously supported me and inspired faith.

I do not remember my first meeting with Borys Gudziak - he seems to have been outside Ukraine for several months when we enrolled. But there was talk of a vice-rector, a young American of Ukrainian descent, a famous historian and a very nice man. Senior students told about his subject "Christian Spirituality in Postmodernism." Rumors had it that there was a lot of talk about rock music, culture and art, cinema, that renowned writers and musicians, such as Viktor Neborak or Taras Chubai, were guests at lectures... He also played basketball. Thus, many of us already loved him without seeing and considered him our person. All this was happening against the background of freshly gray Soviet heritage, indifference, corruption and officialdom in other educational institutions or elsewhere.

Year after year, the Academy was being built before our eyes, a community of people passionate about one thing was actually being built, and they were already building the Academy, and later the Seminary and the Catholic University... And no one could captivate, infect with an idea like Borys Gudziak. We all felt, and I still feel involved in this great cause. At that time, being addressed in a speech or in a private conversation as a person who will create a new society, a new Ukraine, that the Academy forms the leaders of society - was both distant fiction and motivated and added faith in their strength. The thing I am probably grateful the most is this faith!

One of the most vivid personal memories is a large reproduction of the painting Return of the Prodigal Son by Rembrandt in the office of Father Borys. Gudziak was sitting with his back to the reproduction, and we, three violators of discipline, were standing in front of him, looking alternately at him and Rembrandt's Prodigal Son. This is the feeling when you understand the full importance of the situation and feel a certain comic air at the same time. Although I later connected my life with art and saw a lot of it, and loved it a lot, since then Rembrandt's Return of the Prodigal Son has been my favorite painting, an exceptional one!

* * *

The one who listens and trusts

Books can be written and should be written about Metropolitan Borys because His Person is a great gift for the Church and the nation. Having the honor of serving in the Paris Eparchy of St. Volodymyr, he was always impressed by one of the many skills of Bishop Borys, namely the church administration. The attitude of the bishop, who knows how to LISTEN to priests and laity, is impressive. Probably everyone knows that Bishop Borys is not afraid to TRUST and this is always obvious in His episcopal ministry. It is believed that the present time demands and needs greatness. It is a question of FULL DEDICATION to tasks and COOPERATION - our hero of the day never lacked it. Of course, church administration is impossible without PRAYER. All the working meetings, councils, seminars were always built around the Eucharist. All this created a team in which the role of Bishop Borys is unique because he offset the weaknesses of others with his presence and skills. He motivated others and created synergies with his initiatives and assumed powers.

With gratitude and greetings,

Fr. Ivan Danchevsky, rector of the parish of the Nativity of John the Baptist in Ghent (Belgium)

"Listen, how do I even address him correctly?" - "Do it in a simple way"

Yevhen Hlibovytsky,

founder of the pro.mova analytical center, member of the Univ and Nestor groups

I can't remember how I met Borys Gudziak This happens when there are so many common contacts and common interests that they permeate thousands of capillaries with ideas, meanings, people and combine them long before a formal acquaintance can take place.

The turn of the century, a time of great naivety and great hopes. The whole country is growing up fast and is learning to say words for the first time, to insist on their meaning and to defend their own. The presence of His Beatitude Lubomyr, and Father Borys next to him, "in the team" gives the people of Lviv and Halychyna a feeling of additional empowerment. The UGCC returns not empty-handed to Lviv and Ukraine: together with the English-speaking hierarchs come the competencies of the open world. Living in freedom, without fear, the ability to make one's own decisions and the ability to take responsibility, a primitive understanding of the market, a calm attitude to wealth and the absence of fear of poverty - all this is unexpected knowledge and experience from a very unexpected source. After all, the UGCC was an institution that did not break down under the pressure of Soviet persecution or the opportunistic ideas of reconciliation with Moscow that sometimes came up in the Vatican. And when it came to the unheard-of - setting up of new and capable institutions, we had a feeling that behind the old Ukrainian accent and frequent use of Americanism there is some "secret knowledge" that will almost guarantee that all plans will be realized. On the other hand, the idea that "they definitely did not cooperate with the KGB" allowed the trust to bravely dive into the unknown with his head, without fear of hidden agendas. Trust is the ingredient that makes dreams come true.

This intersection of planes strongly charges the batteries: in Ukraine, the old post-Soviet institutions and the lack of modern ones, but the Church's combination of different worlds creates a living environment far beyond the religious sector. The community around UCU is suddenly developing in dozens of different directions and ways. And Borys Gudziak suddenly becomes the leader of this process in a full range of his roles: Greek Catholic priest, later a bishop, Harvard PhD, public figure, entrepreneur leader, Ukrainian with a global perspective, polyglot and intellectual, as well as a leader of an independent institution which is ready to struggle. He is not afraid to sharply rebuke Yanukovych's SBU from persecuting students or publicly criticize the "Jude" tradition in the Christmas nativity scene. Father Borys inspires, nourishes and encourages.

"The phrase "Ukrainian Catholic University" contains the biggest challenge in the last word," I jokingly say to Father Rector Borys Gudziak in one of our conversations after the start of business school, but before the launch of UCU journalism, about twelve years ago. Probably, with any other head of the university, it would be turned into the Fronde, but this provocation leaves him calm:

"We should not be afraid to go in deep waters," he answers quietly and with a barely perceptible smile.

In a few years, I have introduced Bishop Borys to Ivano-Frankivsk businessman Yuriy Filyuk. He is passionate about the idea to reveal to the business movement and business community the figure of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky as a responsible social leader, a prudent creator of conditions for business development in the Ukrainian environment, who had experienced more acute existential challenges than modern Ukraine. One of my colleagues from Kyiv is watching the conversation, points to Borys Gudziak, leans over to me and asks in my ear: "Listen, how do I address him correctly?" "Just be simple," I answered. In a robe and jeans, they all easily find a common language and talk for a couple of hours over coffee in Urban Space 100 - a public restaurant founded by a community of one hundred Ivano-Frankivsk residents. "Do it! But do not take away God from Sheptytsky," said Bishop Borys.

Being several steps ahead in his challenges, Bishop Borys leaves the UCU as he gets transferred to the Benelux, which - albeit in very different conditions - has many challenges for the UGCC that are commensurate with the challenges of new Ukraine in Donbas. Ukrainian life and social mainstream are in different paradigms. Having revived the community in France and Belgium, he gets his next mission closer to his origins, but even further from Ukraine. Washington, the American capital, where hundreds of Ukrainians are making constant concerted or dispersed efforts for Ukraine's international progress, is next to Metropolitan Borys Gudziak's cell in Philadelphia. We sit and talk in the seminary building a 15-minute drive from the Capitol, where we discuss Ukrainian politics, new research on the impact of historical trauma on values, share the complexities of fundraising, and tell each other how to recover from time zones shift. And, of course, dreams of new institutions, only on an ever-increasing level.

Borys Gudziak is a very attentive listener and a laconic interlocutor. His words weigh a lot in the West but have a lot of warmth in the East. He is sleepless but lively, tired but energetic, busy but bold in his plans. 60? Everything is just beginning!

To be continued.

We invite everyone to send us their memories and impressions of Bishop Borys: ukr@risu.org.ua